How Much Allowance Should You Give Your Child in Singapore? (A Parent Guide That Actually Works)

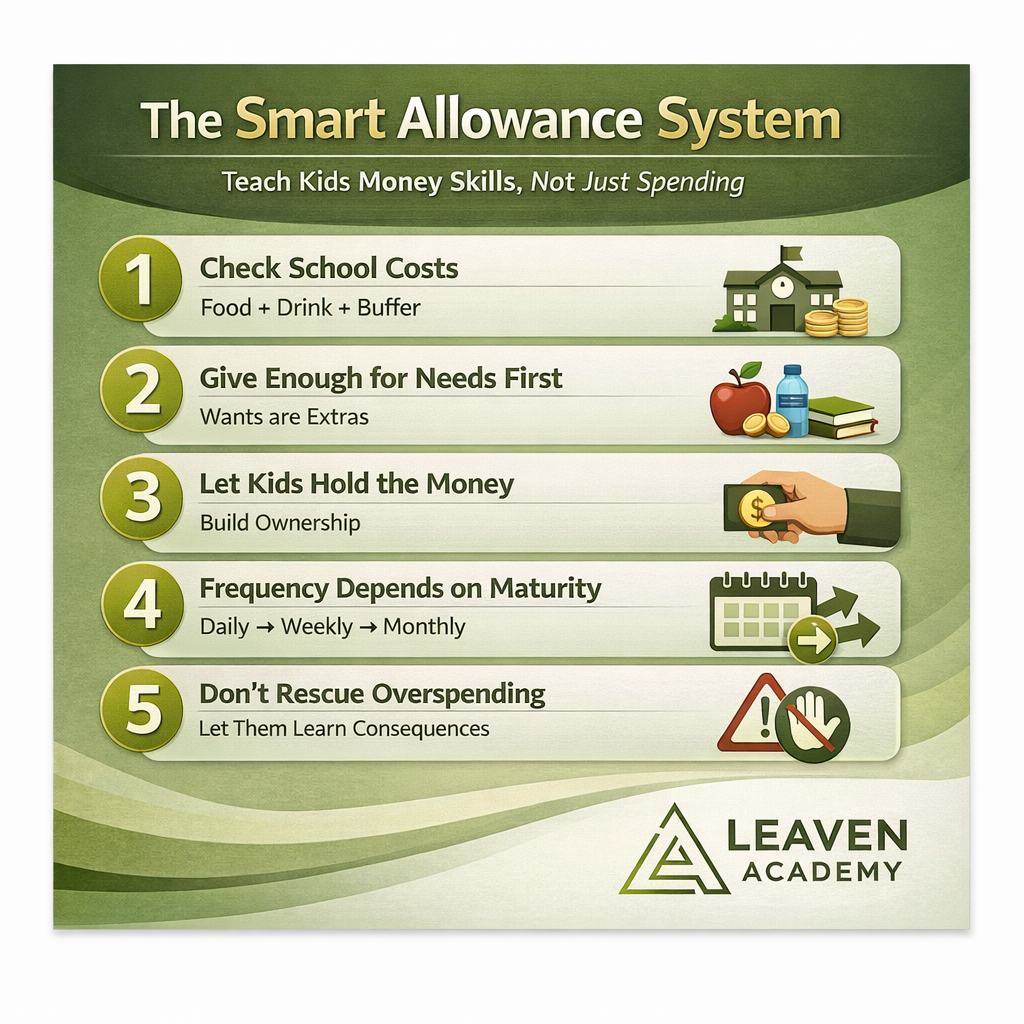

If you’re wondering how much allowance to give your child in Singapore, start by working backwards from real costs: food prices in school, transport needs, and a small buffer for flexibility. There’s no fixed “correct amount”—the right allowance depends on your child’s environment and maturity. The best system is one that trains decision-making: children should handle their own money, practise planning (daily vs weekly), and experience safe consequences when they overspend. Allowance is less about money, more about resource allocation.

The Real Answer: There Is No Fixed “Correct” Allowance Amount

If a parent asks me, “Ernest, how much allowance should I give my child?” I don’t start with a number.

I start with a question:

What does money actually need to cover in your child’s daily life?

That answer depends on:

how expensive the school canteen is,

whether your child needs transport,

and how much independence you want them to practise.

Work Backwards From Real School Costs (Singapore Context)

Here’s what I do in my own family.

My children are in primary school. Before deciding allowance, I checked:

how much a typical dish costs,

how much drinks cost,

and what the daily baseline needs are.

In my children’s school:

food costs around $1.50 to $1.80

a drink costs around $1

So I give $3/day.

This covers:

basic food needs

optional drink

and leaves a small buffer

If they don’t buy drinks (because we provide water), the extra becomes savings. That’s the point.

What Kids Actually Spend Allowance On in Singapore (Reality Check)

Allowance isn’t just spent in school.

From what I observe:

Food (canteen, malls, restaurants)

Snacks (convenience stores with friends: chips, chocolates, slushies)

Games / entertainment (arcade outings)

Trading cards (this is more common than parents realise)

Bookshop spending (sometimes needed, sometimes impulsive)

Transport (especially for older students)

Online purchases (more common among older youths)

One key insight:

Kids don’t just spend on needs.

They spend on identity, belonging, and peer influence.

The 3 Non-Negotiable Rules of a Good Allowance System

If you want allowance to build money skills, these are the non-negotiables I recommend.

Rule No. 1 — Kids must physically “own” the money

Children should have access to their allowance.

Not because it’s convenient.

Because it creates ownership and trust.

If they never hold money, they never practise decisions.

Rule No. 2 — Frequency depends on maturity, not age

Some children can plan. Some cannot.

So the right frequency depends on:

their ability to do basic calculations,

whether they lose wallets easily,

whether they can think ahead.

Rule No. 3 — Parents don’t rescue; kids learn consequences

If children overspend, they must experience a safe version of consequence.

Parents often rush to “top up”, because they don’t want the child to suffer.

But if they never experience consequences:

they never learn to make better decisions.

Allowance is training. Training must include feedback.

Daily vs Weekly vs Monthly Allowance: What I Recommend

There’s no hard rule.

But generally:

Primary school

Start with daily allowance, especially lower primary.

Why? Because foresight is still developing.

When they show they can plan: upgrade them gradually to weekly.

Secondary school

Start with weekly allowance.

Then, if they demonstrate maturity:

spending below their limit

meeting basic needs first

keeping buffer money

…you can scale to:

fortnightly

monthly (only if they’re truly ready)

Monthly allowance works best when they’re ready to allocate larger amounts and manage monthly expenses like transport top-ups.

A Real Story: My Child Spent Allowance “Wrongly” (And That Was the Lesson)

When my oldest child started primary school, he was excited.

He felt empowered.

So he did what many kids do: he spent his allowance on fun things.

Erasers. Pretty pencils. Stickers.

But he didn’t spend on food.

He came home happy, but it became a lesson.

My wife and I decided not to rescue him with extra money.

Instead:

we guided him through safe consequence.

That week, he had to eat what was available at home. Not what he wanted outside.

The key shift happened after: He started meeting needs first. Then using leftovers for wants.

And that is exactly what adults need too.

What to Say When Your Child Says: “My Allowance Is Not Enough”

This is common.

I’ve seen it even in my own family recently.

The mistake parents make is reacting defensively:

“You have enough already!”

Instead, do this.

A calm parental script

“Okay. Tell me what amount would be enough for you.”

Then ask:

“If I gave you that amount every day, how would you spend it?”

Break it down:

food: how much?

drink: how much?

snacks: how much?

savings: how much?

If they can justify it and you can afford it:

increase responsibly.

If they cannot justify it:

“I hear you. But your reasons don’t add up yet. Go back and think it through.”

And if finances are genuinely tight:

be honest.

Transparency builds maturity.

The Core Lesson Parents Should Remember

Here’s my conclusion after years of working with youths and raising my own children:

Allowance is not about money.

Allowance is about:

decision-making

allocation of resources

planning ahead

living with consequences

It trains the exact skills your child will need as an adult.

If you want your child to learn money skills through guided practice—not just lectures—this is exactly why I run youth workshops that train decision-making in real scenarios.